Religious and political historians of 17th/18th century Britain and Ireland are well aware of the long-running conflict between the ‘latitudinarian’ and ‘high-church’ factions in the Anglican Communion. However, many historians of philosophy are entirely unfamiliar with these terms. To historians of philosophy, religious debate in Britain and Ireland in this period is a conflict between Christians and deists/atheists, in which differences among Christians are either entirely invisible or of secondary importance. This is unfortunate, first, because this internal Anglican conflict can shed light on some familiar philosophical texts and debates and, second, because there is a lot of interesting philosophy currently languishing in obscurity that is connected with this conflict.

The terms ‘latitudinarian’ and ‘high-church’ are, at least to some extent ‘actors’ categories’. That is, 17th and 18th century Anglican writers would recognize the terms and have opinions about who belonged to which categories. Both terms were often used pejoratively, but instances of self-ascription can also be found in both cases.

The conflict between these two groups grew out of the effective loss of a national church, in both England and Ireland. (Since the Church of Scotland remained Presbyterian even after the Restoration of the Monarchy, the situation was rather different there.) At an earlier stage the Church of England and Church of Ireland had been understood as national churches—that is, membership in them had been considered part of citizenship in the nation. On this conception, dissent from the church is ipso facto disloyalty to the government, and the existence of any other religious group in the nation is a threat to the national order. This conception played a role in setting up the Wars of the Three Kingdoms: it was not possible for Anglicans and Puritans (and Catholics) to “live and let live” because the unity of the nation, it was thought, required a single church to which all citizens belonged.

Following the Restoration, it came to be accepted that some degree of religious diversity was going to be a permanent feature of the landscape. However, Anglicans continued to defend their status as the established church, that is, the only church sponsored and supported by the government. (The Church of England still enjoys this status today.) The core questions are, first, why should there be an established church at all? and, second, what should be done about the other religious groups?

The latitudinarians were for the most part politically aligned with the Whigs and controlled most of the important episcopal sees from the Restoration on. They generally accepted the modern liberal idea that government is concerned with temporal goods like property and security and so forth, rather than spiritual goods like salvation. Within this scheme, state support of the church is justified because it is not enough for the good of the country that citizens refrain from evil actions; citizens must be positively virtuous. The established church serves as an arm of the state for promoting virtue among citizens. It is a kind of mirror image of the justice system: the justice system punishes people who do wrong, while the church encourages people to do good. Most latitudinarians would deny that this is all that the church is about (the church is certainly concerned with eternal salvation), but it is this benefit to the state that, according to them, justifies the state’s support of the church.

The church, on this view, will be more effective the more people are in it. To this end, the latitudinarians propose a twofold strategy in their relation to non-Anglicans: toleration and comprehension. Toleration simply means that no effort is to be made to compel people into the church. The usual justification for this is that only sincere belief is really productive of virtue and salvation, and sincere belief cannot be coerced. Comprehension means that the church is to be made as broad as possible, insisting only on the bare minimum of beliefs and practices that are necessary to virtue and salvation, so that as many people as possible can, in good conscience, join themselves to the established church. Anglican polemicists (on both sides) usually assume that belonging to the established church is the default position (even with toleration, after all, life is easier for those who belong to the dominant religious group) while dissent requires strong reasons. The idea of the latitudinarian policy of comprehension is to leave as few reasons for dissent as possible.

High-church thinkers, on the other side, were generally allied with the Tories and, while they held some positions of importance in the church, never held the see of Canterbury. They generally believed that, insofar as the end of government is the good of the people, this included their spiritual good, and this was the basis for the government’s promotion of the established church. They usually accepted toleration only reluctantly, not disavowing persecution of religious minorities in principle, but only claiming that it was not expedient at present.

In the remainder of this post, I want to outline what I see as two contrasts in terms of general philosophical approach between writers on the two sides.

Old vs New

One characteristic of latitudinarianism that was recognized early was their friendliness to the ‘new philosophy’. By the turn of the 18th century, this meant primarily the philosophy of Locke and Newton. (Newton’s friend Samuel Clarke was one of the leading latitudinarians in this period, and every one of the early Boyle lecturers was both a personal friend of Newton and a latitudinarian.) High-church writers, on the other hand, favored ancient and Medieval sources.

As is always the case with general characterizations of parties, sects, or schools of thought, there is a serious danger of oversimplification here, but the contrast can be brought out by contrasting the latitudinarian philosopher George Berkeley* with the high-church philosopher Peter Browne. In the manuscript version of the Introduction to the Principles, Berkeley twice quotes Aristotle in the original Greek (!) and also compares his view to that of certain ‘School-men’, but these references are scrubbed from the published version and Locke is the only author quoted. In the later works Alciphron and Siris, Berkeley makes plenty of references to ancient and Medieval philosophy, but he is careful not to treat these as authorities. The approach is thoroughly modern and if any ancient or Medieval ideas are taken up, they are taken up as insights to be incorporated within a modern framework.

Browne is just the reverse. He agrees with Locke on a number of points, and sometimes uses language similar to Locke’s, but he is quite clear that his intention is to reject Locke’s modern ‘ideist’ framework. He says, in fact, that “the University … [has been] unhappily poysoned by an Essay concerning Human Understanding” (Divine Analogy, p. 127). His position is really a neo-Thomist one, though sometimes framed in Lockean language, and, especially in his last work Divine Analogy (1733), Browne clearly treats ancient and Medieval Christian writers as authorities in preference to modern writers whom he rejects.

As another complicating factor we should add that many high-church philosophers, including John Norris and Mary Astell, have a very favorable attitude to Descartes. However, like many theologically conservative Cartesians (e.g., Malebranche and Arnauld), these philosophers tend to like Cartesianism precisely because they see it as bringing Augustinianism forward into the modern age. So, as a rough characterization of the ‘feel’ of high-church vs. latitudinarian polemics, it seems to me to be correct to say that the latitudinarian writers are modern and high-church writers are anti-modern in their approach to philosophy.** Within the high-church party, Browne is an extremist while Astell is a moderate, and one of the many places where this is manifest is in their attitudes to modern philosophy.

Authority and Individualism

A second contrast we can draw, which is more directly connected to the political implications of the views, regards authority and individualism. Latitudinarians, as I indicated above, accept at least some parts of the modern liberal political picture. They tended to be moderate Whigs. (Berkeley, though a latitudinarian in his religion, was a moderate Tory in his politics—a combination that was almost unheard of in England, but less unusual in Ireland.) The natural tendency of Locke’s political philosophy was toward disestablishment of the church, and some radical Whigs in the early 18th century did go so far as to advocate this. Obviously the latitudinarians needed to oppose this tendency, and they did so by means of their argument about the utility of religion for promoting civic virtue. Still, latitudinarian thought was strongly individualistic in both religion and politics. Following Locke, many latitudinarians thought that one key reason in favor of toleration was the (alleged) fact that it is impossible to believe on command. I can only believe something insofar as it appears to me to be true. (This idea receives a lot of emphasis from Edward Synge, the leading Irish latitudinarian.) Religious belief is then seen as the product of an individual following his or her reason where it leads. This means that latitudinarian philosophy needs to focus on providing direct arguments in favor of particular doctrines so that the reader’s own reason will lead her to the truth.

High-church writers typically take the notion of authority much more seriously, and are more inclined to defend their positions by arguing that the reader ought to accept certain authorities. Many, including Browne, do insist that it is possible to believe on command and that political or religious authorities may legitimately issue such commands. Again, Astell’s position is moderate. Nevertheless, the question of the scope of such authority is a central question in her philosophy. She is moderate insofar as she restricts its scope and insofar as she emphasizes the role of individual judgment in determining when to submit to which authorities. Still, despite the rhetoric of individual judgment, much of The Christian Religion is about how to distinguish between just and unjust authorities, so that we may submit to the just authorities (who derive their authority from God) while rejecting the unjust. Authority, including authority over belief, remains a major theme.

Putting these two contrast together, I think, points to one reason why it’s worth caring about the way philosophy emerges in this conflict. It can seem that the high-church faction, insofar as they are conservative and anti-modern, are ‘on the wrong side of history’ and irrelevant to philosophical progress. But this is not so, for a variety of reasons. In the first place, well-known modern philosophers like Locke often endorse pretty extreme forms of epistemological individualism and write as if they can’t conceive of alternatives. The move today toward social epistemology, with worries about testimony, expertise, and the knowledge possessed by groups or institutions is a reaction against this. But the fact is, Locke and friends can conceive of alternatives. Indeed, many of their contemporaries, drawing on Medieval sources, advocated alternatives. Furthermore, these high-church thinkers were in no position to just take authority for granted. After all, they had to argue against Locke and friends and they also had to justify the Reformation. So the question of which authorities we should follow when and why were very much alive for them.

(Cross-posted at blog.kennypearce.net.)

Notes

- Philosophers who are aware of this dispute have sometimes mischaracterized Berkeley as belonging to the high-church faction. I am currently working on a book interpreting Berkeley as a latitudinarian. This was the occasion for this post.

** Anti-modern approaches can never be the same as pre-modern approaches. To say that a philosophers, like Peter Browne, is anti-modern is to say that he is reacting against modern philosophy by trying to bring back Aquinas and friends in the age of Locke. Browne, however, is acutely aware that he’s living in the age of Locke.

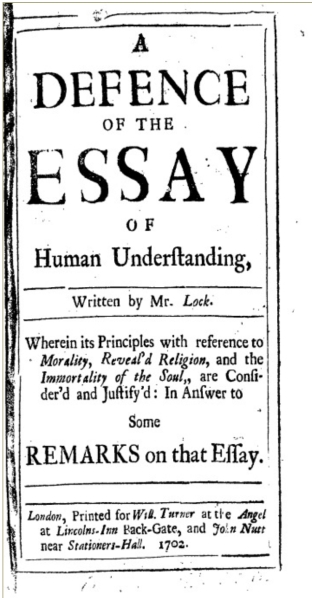

We do not have demonstrative knowledge, without revelation, that the soul is immortal, according to Cockburn’s reading of Locke. She is critical of attempts in natural theology to arrive at the immortality of the soul through routes such as arguing for the soul’s immateriality. It “may be dangerous” to require the soul’s immortality to depend on its immateriality because some people will fail to follow a good proof; arguments (even very good ones) affect people differently. Putting the argument for the soul’s immortality on “false or uncertain grounds” is an aid to those who oppose the soul’s immortality (Sheridan 63-64). Those who want to defend “the future state” (which many worried was necessary to keep people doing good in this life) ought not require demonstrations of immortality of the soul that require immateriality.

We do not have demonstrative knowledge, without revelation, that the soul is immortal, according to Cockburn’s reading of Locke. She is critical of attempts in natural theology to arrive at the immortality of the soul through routes such as arguing for the soul’s immateriality. It “may be dangerous” to require the soul’s immortality to depend on its immateriality because some people will fail to follow a good proof; arguments (even very good ones) affect people differently. Putting the argument for the soul’s immortality on “false or uncertain grounds” is an aid to those who oppose the soul’s immortality (Sheridan 63-64). Those who want to defend “the future state” (which many worried was necessary to keep people doing good in this life) ought not require demonstrations of immortality of the soul that require immateriality.